The pandemic has changed the geography of the American economy.

By many measures, red states—those that lean Republican—have recovered faster economically than Democratic-leaning blue ones, with workers and employers moving from the coasts to the middle of the country and Florida.

Since February 2020, the month before the pandemic began, the share of all U.S. jobs located in red states has grown by more than half a percentage point, according to an analysis of Labor Department data by the Brookings Institution think tank. Red states have added 341,000 jobs over that time, while blue states were still short 1.3 million jobs as of May.

Several major companies have recently announced moves of their headquarters from blue to red states. Hedge-fund company Citadel said recently it would move its headquarters from Chicago to Miami, and Caterpillar Inc. plans to move from Illinois to Texas.

To track each state’s progress toward normal since the pandemic began, Moody’s Analytics developed an index of 13 metrics, including the value of goods and services produced, employment, retail sales and new-home listings. Eleven of the 15 states with the highest readings through mid-June were red. Eight of the bottom 10 were blue.

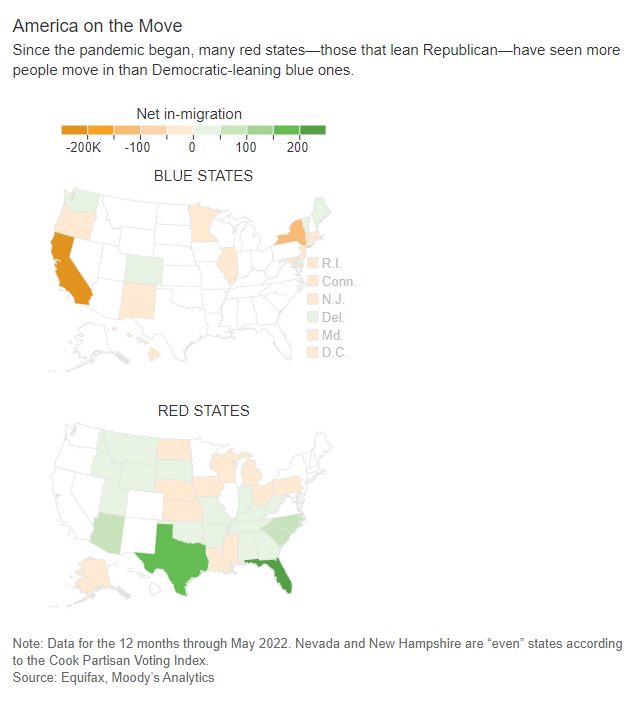

Behind those differences is mass migration. Forty-six million people moved to a different ZIP Code in the year through February 2022, the most in any 12-month period in records going back to 2010, according to a Moody’s analysis of Equifax Inc. consumer-credit reports. The states that gained the most, led by Florida, Texas and North Carolina, are almost all red, as defined by the Cook Political Report based on how states voted in the past two presidential elections. The states that lost the most residents are almost all blue, led by California, New York and Illinois.

Analysts who have studied the migration attributed much of it to the pandemic’s severing of the link between geography and the workplace. Remote work allowed many workers to move to red states, not because of political preferences, but for financial and lifestyle reasons—cheaper housing, better weather, less traffic and lower taxes, the analysts said.

There is no data on what role, if any, political preferences have played in migration decisions. Some researchers have reported that pandemic restrictions played a role for some people who moved. It is too early to know whether the Supreme Court decision on abortion also might affect migration patterns.

The movement is already starting to affect state economies and finances. Florida is on track to register a record budget surplus for the fiscal year that ends June 30, which it attributes in part to new residents. The state is putting most of the extra money into a reserve fund to protect state agencies and residents during the next downturn, while investing in school construction and raising teacher pay, a spokeswoman for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said.

Over the 30 years that preceded the pandemic, globalization and technology had fueled a “knowledge economy” dominated by college graduates who clustered in big city metropolitan areas in the West and Northeast. Property values soared in those areas, while lagging behind in other areas.

The Covid-19 pandemic changed that dynamic.

“I almost feel like the pandemic differs from any other time I’ve seen. There’s definitely a flight to lifestyle,” said Chris Camacho, chief executive of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council, a private consulting group that recruits businesses to Arizona. “Individuals were choosing where to live.”

In a recent survey led by researchers at Stanford University, the University of Chicago and the Mexican university ITAM, about 16% of workers said they plan to stay fully remote, and another 31% plan to adopt a “hybrid” schedule of working in the office part-time and at home the rest. Most of those remote workers are well-paid, white-collar college graduates, according to the research.

“I always had to go to where the job was,” said Sankeerth Bommi, a 40-year-old technology worker from India who emigrated to the U.S. in the early 2000s. When the pandemic hit, Mr. Bommi was living in Los Angeles and commuting to the Pasadena offices of financial-technology company Green Dot Corp., where he is a senior director on a product team. Within weeks, the company told its 900 employees they were free to permanently work from anywhere.

Mr. Bommi moved to Austin, Texas, to be closer to cousins in Oklahoma and Texas, and for cheaper housing. He just bought his first house, where he plans to work once it is built. “This is the first time I’m able to go to the city I really wanted to go to,” he said, as opposed to where his job took him.

In the end, his employer made the same move. The company last year moved its headquarters to Austin, slashing its real-estate and business-travel costs, due to Austin’s central location.

After closing its offices in March 2020, Green Dot routinely surveyed employees about work-from-home policies. More than two-thirds said they didn’t want to go back to the office, said Chief Executive Daniel Henry. The company has just 25 people working out of its new location. The rest are scattered across the country.

In Austin and Houston, office occupancy has recovered faster than in the nation as a whole, with more than half of offices occupied, according to swipe-card data by the security firm Kastle Systems. In the business districts of San Francisco and San Jose, by contrast, only about one-third of office space is occupied, and in Los Angeles, about 40%.

One big reason so many people moved during the pandemic has been a desire for less expensive housing, according to an April report from the Economic Innovation Group, a think tank. By analyzing county-level census data, it found that large urban areas with high shares of commuters lost residents in the 12 months through July 2021. Among that group, large urban counties with the highest median home values experienced the biggest declines.

Small and medium-size cities, suburbs and rural areas—all of which tended to have less expensive housing than large urban areas—all gained residents.

It remains to be seen how many of those moves turn out to be permanent, and whether many recent migrants eventually move back to more urban areas. In recent months, some companies have been urging remote workers to return to the office.

In the 10 states that gained the most people from moves between April 2020 and June 2021, the typical home cost 23% less than the typical home in the 10 that lost the most residents to moves, according to an analysis by the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank.

The states that gained the most migrants levied an average maximum income-tax rate of 3.8% on individuals. Four—Florida, Texas, Tennessee and Nevada—charged no income tax at all. The 10 states that lost the most residents to moves have an average tax rate of 8.0%.

Now that more employees are leaving expensive blue regions or working remotely, employers themselves have more freedom to move to lower-cost areas.

“I can’t force people to move. You can’t do that anymore,” said Chris Rouland, chief executive of Phosphorus, a privately held cybersecurity firm.

He started the company in 2017 and opened small offices in Atlanta and Carlsbad, Calif. When the pandemic hit, he said, his 14 employees began working remotely—many moved from California to lower-cost states—and soon told him they wanted to do so for good.

Mr. Rouland gave them that option. Last year, he moved the company’s headquarters to Nashville, to take advantage of lower taxes and a higher standard of living, he said, while allowing most employees to work remotely.

“They started to think about where they’d actually like to live based on quality of life, based on taxes,” Mr. Rouland said. “And for us, we looked at where we wanted our business to be and, honestly, where I wanted to live. For me, it was literally the first time in my life I chose to work someplace”—as opposed to having to move to an employer. Earlier in his career he had moved to New York City to work for Lehman Brothers and to Atlanta to work for a tech startup.

Mr. Rouland has closed the California and Georgia offices and now employs 40—seven in the Nashville office with the rest spread around the country. Yet over time, he said, he has become less enthusiastic about remote work, and he has begun urging workers to consider moving to Nashville and returning to the office.

Tennessee’s economy has benefited from such moves. Its unemployment hit an all-time low of 3.2% in April, according to federal data dating from 1976. Its workers saw some of the biggest gains in weekly earnings among all states last year. Its economy grew by 8.6% last year, leading all states. Corporate and sales tax revenues are rising.

Gov. Bill Lee, a Republican, has proposed increases in teachers salaries, freezing tuition at state colleges and hiring more state troopers.

People who moved during the pandemic tended to go to areas with fewer pandemic-related restrictions, such as school and office closures and event cancellations, according to a paper from researchers at Vanderbilt University and the Georgia Institute of Technology.

In general, red states were less likely than blue ones to impose mask or vaccine mandates, social-distancing restrictions or remote schooling. Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools fell nationally during the pandemic, but the sharpest drops occurred in school districts that had more days of remote learning, according to a recent American Enterprise Institute study.

California’s public-school enrollment has fallen 4.4% since the pandemic, according to American Enterprise Institute. In Oakland, the school board recently voted to close schools because of declining enrollment.

Florida saw a surge in new residents, many from the Northeast, where Covid-19 related restrictions such as school closures were stricter.

At the Ohana Institute, a private school in Florida’s Panhandle, for kindergarten through 12th grade, the waiting list for students grew from 95 just before the pandemic to 393 last fall, Executive Director Lettye Burgtorf said.

Mrs. Burgtorf said the school fielded requests from hundreds of parents around the U.S. who wanted to move to Florida to be closer to the beach. Many were also unhappy that their children’s schools in other states had moved to remote learning. The Ohana Institute went remote for several weeks, then reopened, with mask mandates. “The parents were really like, ‘We cannot educate our kids at home,’ ” Mrs. Burgtorf said.

For years, a real estate boom in coastal cities made many families wealthy because their homes appreciated. Now, that is happening in red states. Florida led all states with a 31% jump in the median home price in the 12 months through January, with prices soaring in the Panhandle.

Such price increases can narrow the cost-of-living differential with the blue states that the migrants are fleeing, and increase living costs for longtime residents who don’t own homes,

These days, Mr. DeSantis’s spokeswoman said, one of the top complaints the governor’s office receives is soaring rent.